When was the last time you were tucked tightly into a linen cocoon and read a story by a parent or a loved one?

Although I can’t pinpoint the last time my mother read to me in my bed—as she would often climb into the twin-size frame next to me—I do remember specific nights and the stories that were told. I remember reading a scratch-and-sniff story and smelling the gingerbread houses illustrated on the page. I confess falling asleep while my mother started chapter two of the new Harry Potter novel. And I remember being terrified of a book read to me about rabies—gifted to us by a friend who was a nurse.

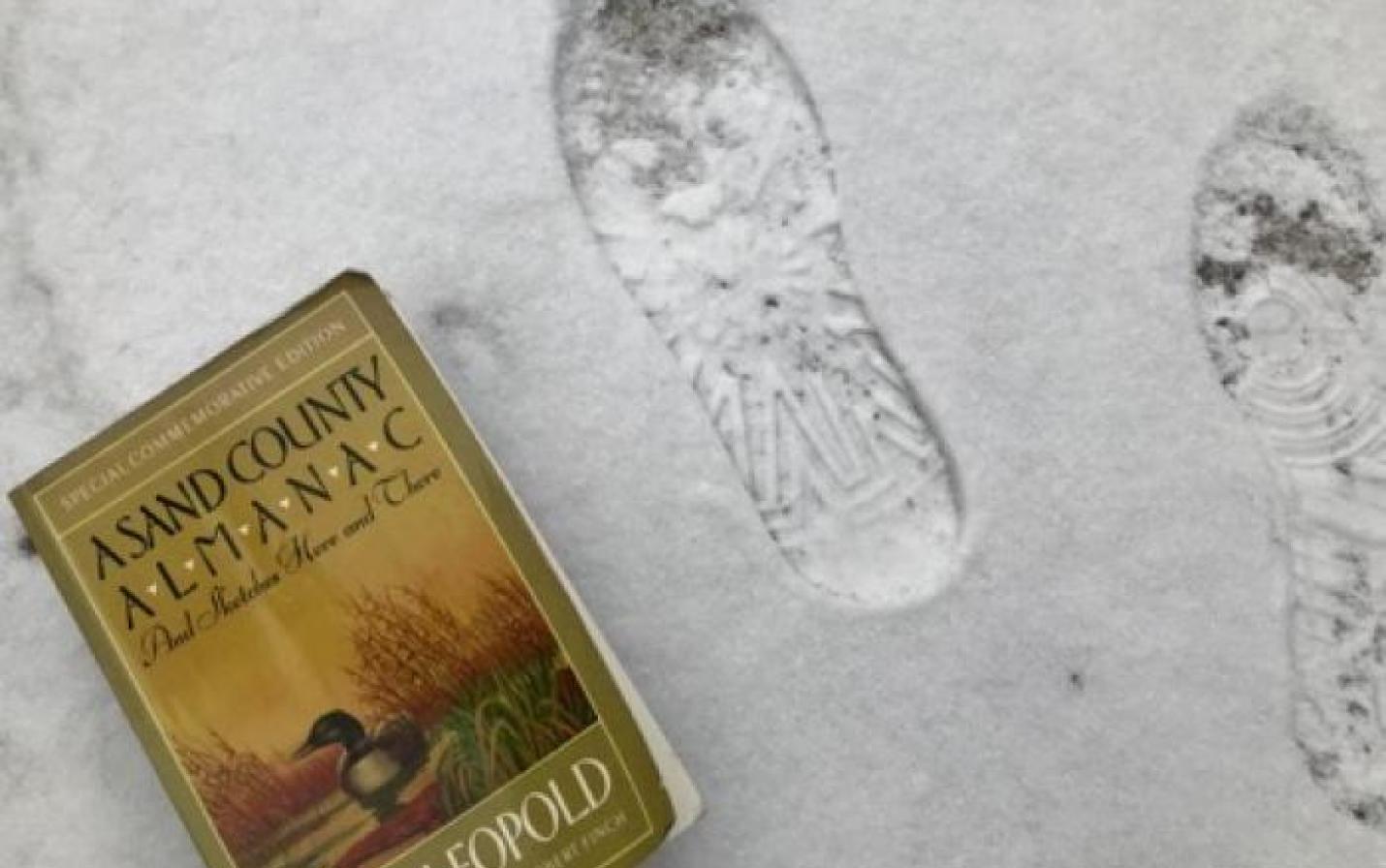

Being an adult, I don’t always have the energy to read before I fall asleep even though it was such an integral part of my childhood. Therefore, we need to take advantage of the time we do have. We aren’t kids anymore but that doesn’t mean we can’t give this time to them. So, get your young loved ones into their pajamas, tuck them into that linen cocoon, and take out A Sand County Almanac by our beloved, Wisconsin-exploring Aldo Leopold. I’m challenging you to bring the outdoors into the bedtime routine that children hold so dear to their hearts. I won’t vouch for the whole book to be read, but one specific story: “January Thaw.” It is the story that begins A Sand County Almanac and depending on your copy, is about three pages long. The complete almanac—dual-defined as a handbook or calendar containing information—is roughly 200 pages and comprised of three parts made up of short stories, a few essays, and some scattered sketches.

Leopold’s first story, “January Thaw,” takes its readers on a journey, following in the recent snowy footprints of a skunk. On this walk, Leopold startles a mouse and sees tufts of rabbit hair. (Spoiler: Both end up in the stomachs of a hawk and an owl, respectively.) Although at the end Leopold is unsuccessful at locating the skunk’s whereabouts, he nonetheless persists to wonder where it could be.

Taking vocabulary into consideration, I would recommend this story to a school age audience, but please don’t see the vocabulary as a barrier between your little reader and Leopold. This is a chance to ask them questions that lead them along the story like the footprints of the skunk. “Do you leave tracks in the snow like these animals?” or “Do you know what a mink looks like?” for example. The short story incorporates the food-chain, as well.

In full disclosure, Leopold finds a bloody concave in the snow paired with a snowy track from owls' wings. But again, this shouldn’t deter from sharing the story. It shows the interdependency our environment and its inhabitants have. The melting snow has destroyed the underground burrows the mice have made. This is what leads to the hawk to drop “like a feathered bomb into the marsh” and to eat the exposed mouse. These scenes aren’t gory. But they are honest. And don’t we want future generations to understand nature instead of romanticizing it into something that it isn’t? Nature isn’t perfect. But guess what? It is still beautiful and intriguing and fun! This is the lesson Leopold teaches us.

So, let’s read “January Thaw” from A Sand County Almanac to instill a love, as well as an understanding, of nature into children. The story doesn’t have to stay in the bedroom, either. You can take it into the outdoors and find the tracks and the evidence animals have left us with our little ones too.

Perhaps years from now, when they don’t have the energy for bedtime stories anymore, they’ll reminisce on a winter night when a loved one read them a story. A story about following behind the footprints of a skunk. And they'll remember being zipped snug into a jacket by that loved one to go on an animal tracking adventure of their own. Hand in hand. Together.

Marissa Widdifield is a student of environmental literature at University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.