Birdwatching is gaining the perspective of another.

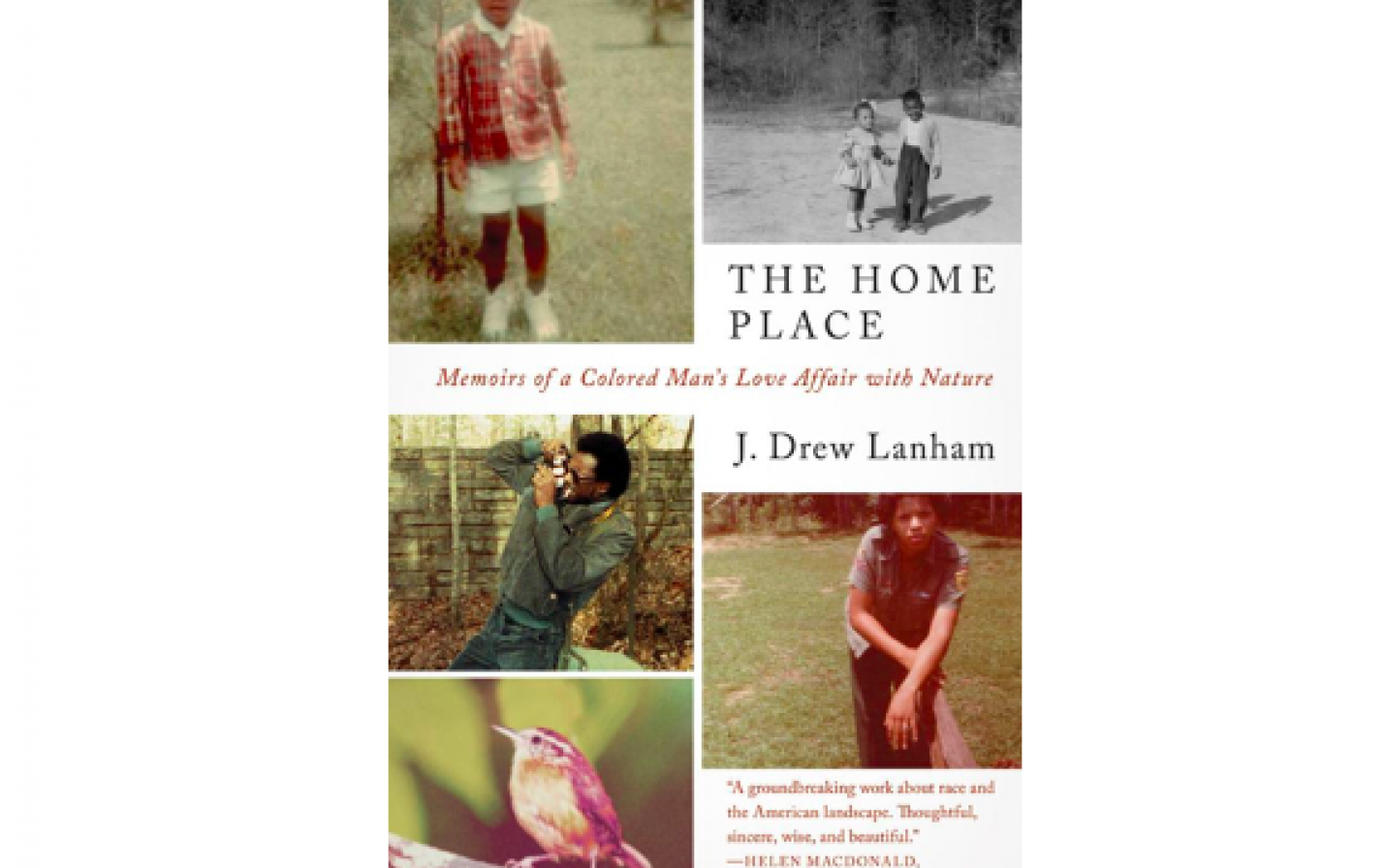

J. Drew Lanham does just that in his 2016 book The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature.

Dreaded futures are the product of a lack of options. As a Black man in college, J. Drew Lanham, was given two future possible careers: a physician or an engineer. His dream was to be an ornithologist. Living off of society’s expectations –and a scholarship—he chose engineering. His counselor suggested that “engineering would help [him to] earn [a] lifestyle to enjoy birds as a hobby” (137).

Turns out his dream wasn’t to fulfill someone else’s lifestyle. After three long years, his journey as an engineering major ended, and his ornithology career began.

Researching bluebird sex proved to be a hot topic for Lanham. The heat coming from the sweltering South Carolina July, of course. His summer was spent wreaking havoc on baby bluebirds’ lives by “measuring, banding, bleeding the little pine feathered chicks to see if the brilliant blue male that typically attended each box was indeed the little one’s DNA daddy” (135). While studying the bluebirds, Lanham was also able to better understand people.

Science has never existed in a vacuum. During his research, Lanham noticed that our stereotypes about how people should behave bleed into our ideas about how animals should behave. That bluebirds should be monogamous. That a Black man would want to be an engineer.

As a novice birdwatch, I share J. Drew Lanham’s love for birds and nature. Sitting in front of a computer it is easy to fall in love with the pastoral scene of “the biggest, bluest sky, surrounded by singing birds in fields and forests that stretched as far as the eye could see” (138).

Yet, as a White birdwatcher, I will never share all of his experiences. His doctoral field research study sight was vandalized with “three raggedy, red spray-painted Ks” (156). It is no wonder that “in remote place fear has always accompanied binoculars, scopes, and field guides as baggage” (156).

The racist ideas within our society mixed with his love for nature casts him as, “a raven in a horde of white doves” (141). The straightforward struggle in nature draws him in. The simplicity in life or death can be comforting, “There is no evil in nature” (142). He wonders what it means to truly be wild and to be free of judging stereotypes, and the emotions that follow.

Leisurely work can turn dangerous when birding outside a house “with the Confederate flag proudly displayed” (151). Lanham often has to walk that fine line between doing his job and getting hanged. This balancing act is done without the safety of a net. His job is to wait, watch, and listen for birds. Yet, at this stop, it is difficult to tell if he is the one watching. The work becomes less leisurely.

At earlier stops, he is met with perfect scenery of “an old apple orchard...Warbling blue grosbeaks, buzzing prairie warblers, and chattering yellow breasted chats” (153). The birds pay no attention to him.

One haunting day Lanham and his coworker were followed. Questioning his career choice and praying to survive. His safety compromised to check field traps.

In another incident, he was forced to abandon his work on “rose-breasted grosbeaks, golden-winged warblers, and forest management in the Southern Appalachians” because a white supremacist group decided to have a ‘meeting’ near his research site (156).

Working in remote places is a job expectation for a wildlife biologist. Lanham started doubting his future credibility as he was repeatedly forced to choose safety over his career.

Lanham continues to persevere. Today he is a professor of wildlife at Clemson University.

“The wild things and places belong to all of us. So, while I can’t fix the bigger problem of race in the United States -can’t suggest a means by which I, and others like me, will always feel safe- I can prescribe a solution in my own small corner” (157).

Go birdwatching with J. Drew Lanham, peer through his binoculars and see what our world looks like.

Anna Houston is a student of environmental literature at University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.